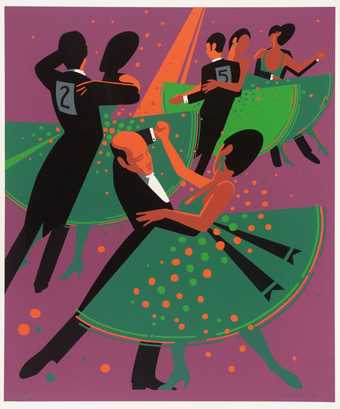

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

Dance Hall Scene (c.1913–14)

Tate

Dancing and music

Music, dance and visual arts have often gone hand in hand. These artists found ways of getting the rhythm of dance on to the canvas.

Nicholas Monro

Dancers (1970)

Tate

Paula Rego

Drawing for ‘The Dance’ (1988)

Tate

William Blake

Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (c.1786)

Tate

Arthur Rackham

The Dance in Cupid’s Alley (1904)

Tate

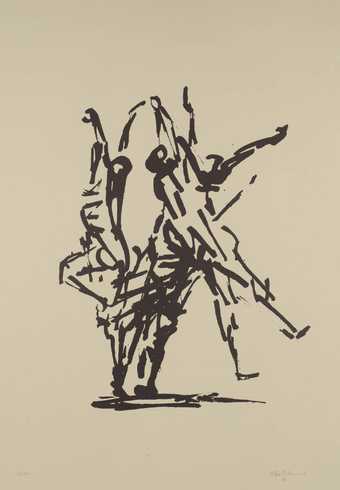

Oliffe Richmond

Dance (1966)

Tate

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

Dance Hall Scene (c.1913–14)

Tate

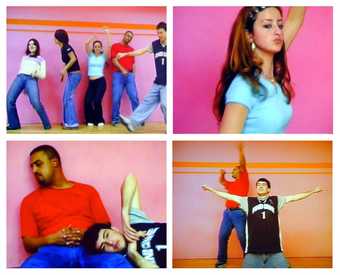

Phil Collins

they shoot horses (2004)

Tate

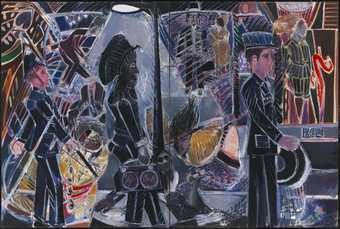

Denzil Forrester MBE

Three Wicked Men (1982)

Tate

Other artists have looked for ways of representing rhythm on film. For Christian Marclay’s Video Quartet he painstakingly spliced together parts of Hollywood films. The four huge video screens and their soundtracks cut and change, but together they create an amazing pulsing rhythm.

Christian Marclay

Video Quartet (2002)

Tate

Douglas Gordon filmed the conductor James Conlon as he conducted the soundtrack to the film Vertigo. He did not show the orchestra , just focused on the movements of the conductor. He determined the rhythm of the cuts in the film by the rhythm of the music in the score.

Douglas Gordon

Feature Film (1999)

Tate

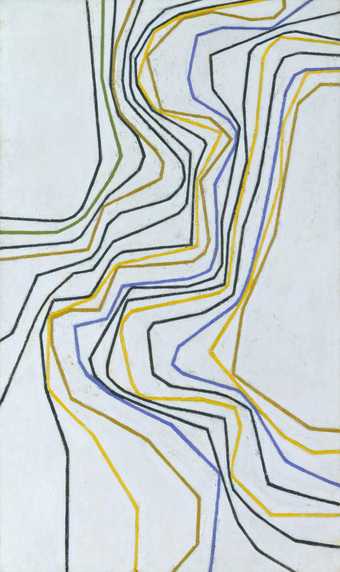

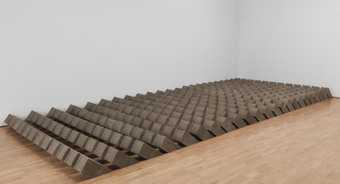

Rhythmic forms

Many artists find rhythm in pulsing shapes and lines. Certain colours put together can seem to vibrate.

Other artists, like Barbara Hepworth, have been inspired by the swooping, curling rhythm of the sea or the rolling landscape.

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Pelagos (1946)

Tate

J.M.W. Turner created many atmospheric paintings of rough seas. They capture the rhythm of crashing waves and rising swell.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Rough Sea with Wreckage (c.1840–5)

Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge - Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (exhibited 1843)

Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Sketch for ‘East Cowes Castle, the Regatta Beating to Windward’ No. 2 (1827)

Tate

After Joseph Mallord William Turner

A Fresh Breeze (after ‘Sheerness and the Isle of Sheppey’) ()

Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner

George IV’s Departure from the ‘Royal George’, 1822 (c.1822)

Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Ships Bearing up for Anchorage (‘The Egremont Seapiece’) (exhibited 1802)

Tate

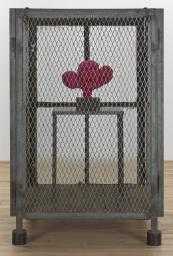

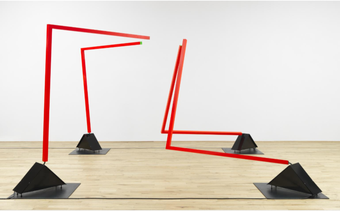

Moving art works

Some artists make art that moves (and maybe moves you too).

In Jenny Holzer's BLUE PURPLE TILT short phrases flash up and down the seven LED displays. They look like the signs you might read on a train or bus, telling you what the next stop is. But these signs repeat phrases and words Holzer has found in books, poems and other public texts. The seven displays show the same phrases at exactly the same time, creating a mesmerising rhythm.

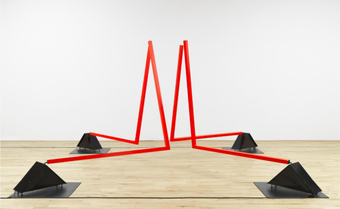

Peter Logan

Square Dance (1970)

Tate

Peter Logan, Square Dance 1970, Tate, © Peter Logan

Peter Logan, Square Dance 1970, Tate, © Peter Logan

Peter Logan’s Square Dance has four moving arms that move in a simple set of movements. His first version of this work was hand-operated. As he refined the work over different versions, he worked with an engineer and an electronics company to make the movements automatic.

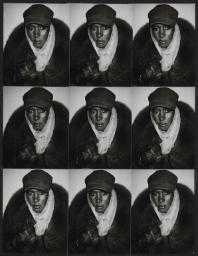

Repetition and everyday motions

There is rhythm in repeated action, and a rhythm to life. Sometimes we talk about circadian rhythms, the everyday rhythm of the body: waking, eating, sleeping. Repeating images create a sense of rhythm of their own.

Andy Warhol

Grace Jones (1986)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© 2025 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

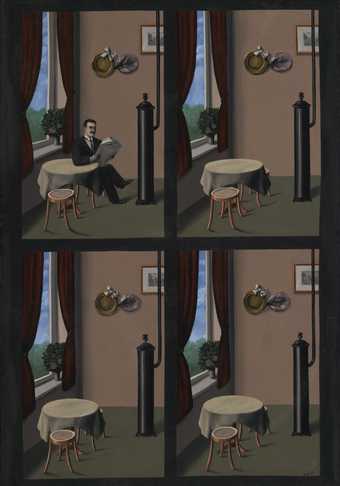

René Magritte

Man with a Newspaper (1928)

Tate

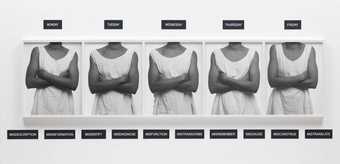

Lorna Simpson

Five Day Forecast (1991)

Tate

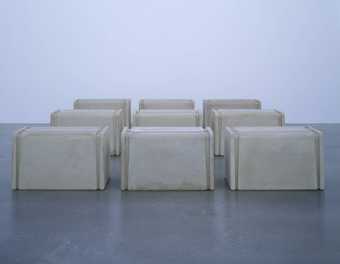

Kader Attia

“Untitled” (Concrete Blocks) (2008)

Tate

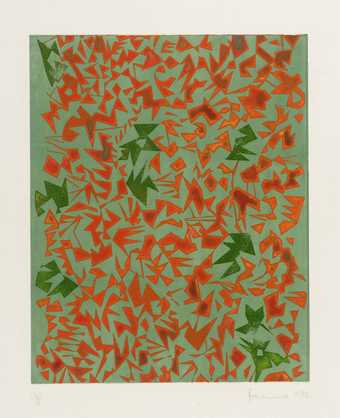

Felicia Browne

Print of an abstract repeated design ()

Tate Archive

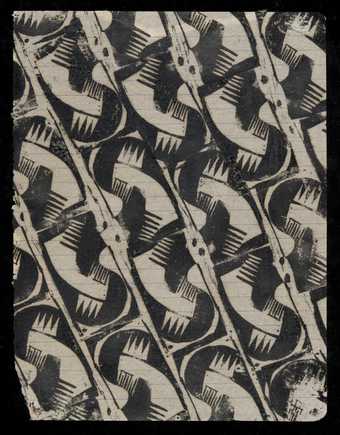

Rachel Whiteread

Untitled (Nine Tables) (1998)

Tate

Stairs

Do you clatter down the stairs: bang, bang, bang, bang, bang!? Or do you come down with a trot? Can you tell who’s coming up or down the stairs from the rhythm of their steps?

Gillian Carnegie

Hanser (2010)

Tate

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

The Golden Stairs (1880)

Tate

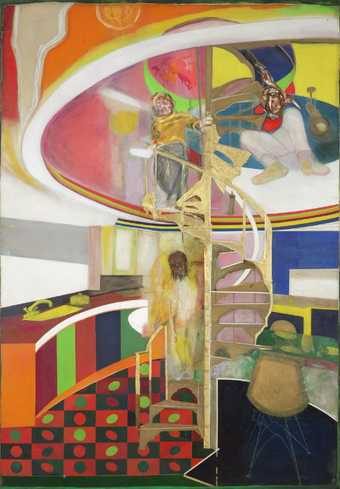

Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA

Mirror (1964–6)

Tate

Everyday actions

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds consists of about ten tonnes of hand painted porcelain sunflower seeds. The sunflower has lots of meanings in Chinese society. The seeds themselves are an everyday snack. As he said:

'Handfuls were carried in pockets, to be consumed on all occasions both casual and formal.'

So this pile of seeds can remind us of the everyday feeling of turning something over in your pocket, or of chewing and swallowing. Or maybe it reminds us of the people in Jingdezhen in China who painted every single one of these seeds by hand. What rhythm did they find in their actions?

Ai Weiwei

Sunflower Seeds (2010)

Tate

Sometimes repetition is comforting. Louise Bourgeois’s 10 am is When You Come to Me shows a series of paintings of hands. The hands are Bourgeois’s and her studio assistant Jerry Gorovoy’s. The 10am in the title is the time that Gorovoy would arrive at Bourgeois’s studio or home to begin their working day together. This shows the reliability and familiarity of their daily routine. Bourgeois said about him:

‘When you are at the bottom of the well, you look around and say, who is going to get me out? In this case it is Jerry who comes and he presents a rope, and I hook myself on the rope and he pulls me out.’

Louise Bourgeois

10 am is When You Come to Me (2006)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

Have a go!

Make rhythmic marks

Victor Pasmore

Spiral Motif in Green, Violet, Blue and Gold: The Coast of the Inland Sea (1950)

Tate

Victor Pasmore was interested in using rhythmic movements in his drawings. He used the repeating spiral shape to see what it suggested to him and then created a number of landscapes from these rhythmic sketches. Pasmore was inspired by the teaching of Paul Klee (pronounced Klay). He thought these simple shapes or pure forms should combine with an artist’s intuition to create art.

- First find your rhythms. Get out into the countryside. If you live near the coast, watch waves and clouds. If that’s not for you look at water over a weir, the shapes of hills and valleys, the movement of grasses or crops in fields, stormy skies, a flowing river, or waving leaves and branches.

- Sketch the shapes of the movements or rhythms you see. Are they spirals, circles, ovals? Do they have peaks and troughs, points or corners? How does it make you feel to sketch in this place?

- Decide on your shapes and forms. In your sketchbook, experiment with repeating those shapes over and over again. Use different materials and colours and see what your compositions suggest to you.

- As you work, remember the feelings you had in the place you started. Do your rhythmic sketches have the same feeling? Can you change the colours, sizes or materials to make it feel different?